Author’s note: It’s here. That vile word.

The Runaway

Sundays on our little rice farm didn’t bring no reprieve from work. Especially the first Sunday of every month. The day started about two hour from sunrise. The liquor was still sloshing about in Daddy’s belly when he kicked all his boys out of bed. We had us two days of travel ahead of us as we were set to go from plantation to plantation, delivering fresh wood chippings for their coops and collecting all their shit-licked litter.

Daddy sold the new wood chippings to the fat magpies at well below market price, and the fee for hauling away the fusty chicken litter was near next to nothing. He was running a con on the plantation swill, and they didn’t have no clue that he was in more need of their litter than they were in need of fresh wood chippings. This was the secret to daddy’s record-setting yields on our little farm. He took more bushels per acre to market than anyone in South Carolina. For all we knew, no one in all the world could match him, and he owed it all to his special fertilizer, chicken shit.

There were four plantations within a day’s ride if the woodland lanes weren’t cocked up with tree branches and deadfalls and such. Three of us, Daddy, Charles and me, we would make the looped sore-assed journey and be back by sunrise next. If the trek was met with muck and obstacles, we’d be gone longer. Douglas always stayed behind to tend to the errands we would miss and watch over the property during our absence.

Daddy always had him a time the Saturday’s ‘fore we hit out on our chicken shit run. He’d liquor up good and plenty, more than is his custom, and he ain’t a kind drunk. His fists were employed more times than not, and there weren’t nothing but family to catch ‘em. Douglas was the poor sumbitch who took knuckles the night before we took off on the trip where we’d meet up the advance man. He had an eye swole shut, and his nose had a bend in it that it didn’t have previous.

The thing of beauty that me and Charles woke up to was that daddy had him a fat lip. Our brother by half had swung on the devil incarnate and got him one good lick in. He paid for it with extra punches with extra heat in ‘em, but good lord of firecrackers, me and Charles was tickled to near death to see that someone finally got daddy with a fist to the face.

Charles had him a bruise that run from his right eye to the jawline, but it didn’t dampen his spirits a bit. He was a towering fountain of glee when he set off to give feed to the pigs and chickens. I swear I even seen him do a little dancing about just before he ducked around the corner of the barn.

Amongst the tools and wood chips on the first wagon, Daddy had him under his seat the Mississippi rifle the army issued him during the Mexican War. He weren’t even eighteen when he joined up. As it turns out, his youth didn’t suffer none from much in the way of military fighting because he’d missed any real action by the time his regiment arrived on the banks of the Rio Grande. He served his soldiering without firing a shot at any enemy combatant. If not for a corrupt supply specialist taken payment in return for not collecting government issued weaponry, daddy would not be in possession of his Mississippi rifle some 15 years after his service ended.

I drove the empty side-wall wagon with Charles laid out in the back. He’d take to driving the rig after a couple of hours of shuteye. Some godforsaken hours after that, we’d arrive at the Stephens’ plantation for our first unload and load.

Daddy took the lead and drove his bay toward the tree line. We could walk faster than he had us paced, but he took extra care because our rigs did not have room for spare wheels should shit go bad. The clank of the wagons and the snort of the horses are about the only diversion one can find on such a journey across hell. The cursed ground kicked you up and down and from left to right. Sleeping on such a jostle of a trip was an acquired skill. Wasn’t nobody more talented than Charles when it come to such things. The ground didn’t have no give, and the rigid design of the wagon made the bumps and cracks feel like your backside was getting beat by a hammer. Not a minute of it was a match for the dog-tired hours we’d had spent working on a rice farm in the wetlands of Charleston. Both Charles and me could sleep through most anything.

I trained my eyes on the back of daddy’s leather-neck as we crawled along. Dark stiff hairs poked out of his yella sweat-stained shirt and curled around the collar. He wern’t a well-groomed man, and he didn’t have no care for his appearance. Didn’t have no time to care about such matters. He sure as shit didn’t give a care how momma got along in her manner of dress nor his demon boys neither. To say we was outfitted in rags is to not know rags would be fancy duds that we Tennysons couldn’t near afford. Looking at the back of his neck, it struck me that Daddy didn’t care for a goddamn thing. Not even for the profit he chased like a raving lunatic. Daddy only lived to fill his minutes with misery. He was habituated to it.

I swatted at a mosquito and redirected my attention to its effortless aerobatics to my left. I watched it dart up and somersault to the right and circle down in a diagonal before I even expelled a breath. The quickness of the flighted creature would have been impressive if it not such an annoying bloodsucking vexation.

As I studied its change in direction once again, I spotted the figure of a woman pressed against the trunk of a tall as shit sycamore tree. She was black. Black enough to get lost in the gloom of the pre-dawn hours. The white fringe around the collar of her blue dress was the only thing that give her away. She clasped her hands together under her chin, revealing a rope coiled around her wrists. We locked eyes, and I could see they was floating in a pool of tears. She slowly shook her head, pleading with me not to give attention to her. I smiled, nervous-like and give her a single nod to indicate that I would not let on that I seen her. I can’t explain what was rolling around in my head, but I felt a kinship with the woman that before I never give thought to. Me and her was bonded to a life of labor we was born into, to men most awful, in a place where we weren’t pitied for our bad luck as much as mocked for our lack of rule over our own fate. I suppose the difference being that a day would come where I’d age out of my hell. If I lived that long. That rope around her wrist would remain ever-more until she give feast to the rot of death.

“Eyes forward, boy.”

I’d become so turnt around by the mystery of the woman I’d nearly forgotten daddy was ahead of me. I spun around to see him shift his eyes from me to the direction I’d been looking, and then he trained his eyes back on me. With a voice made hoarse by exhaustion and panic, I said, “Yes, sir.”

“You can’t handle the rig right, wake your brother.” He turned his attention back to the narrow passage.

“I can handle it right, sir. Eyes forward, sir.” A breath escaped my lungs that I didn’t know I’d been holding. I immediately wondered if Daddy had got an eye on the woman. If he had, I was pleased he didn’t elect to stop and investigate the piss-poor luck that left her in the middle of the woods before sunrise with her hands bound up with rope. She was better off with him moving on and leaving her fortunes in the hands of the unknown because he weren’t nothing but a known terror.

I held an itch to turn back around and give her one last look. I didn’t dare do it for fear he’d catch me. I hoped against hope she not move until we were long out of earshot. If daddy had seen her, he was pretending he hadn’t, so our travels wouldn’t be interrupted. If she were to raise attention on herself, he may decide that there was profit enough to be had in seizing a black woman bound by ropes. Someone had lost their property, and they’d most likely pay a handsome reward for her return.

We hadn’t traveled a quarter mile from the spot of the runaway when two men armed with holstered handheld repeaters plodded towards us on horseback. The two fellas represented two opposing shapes. One was as round as a ball of yarn, while the other was as narrow and crooked as a sapling. Both hadn’t seen the opportunity to scrub themselves of layers of grime and whatnot for what appeared to be weeks going on months. The smell of them even give trouble to the horses that carried them.

The bone skinny one raised a hand as they both guided their horses to block our path. “Ain’t you folks up and about early? Didn’t expect to see no one this time’a day.”

Daddy held his bay’s reins with one hand and eased the other one to rest on the bench. He was calculating his movements to his Mississip’ should the occasion be so needed.

“Got deliveries to make.”

The skinny one craned his neck to look at the massive pile of wood chippings. The round one directed his horse off the path and slowly marched his colt to the wagon I was driving.

“This your boy?” he asked.

“It is. You fellas are out of place yourself.”

The skinny one laughed. “You can say that again. If our foreman would have hired right, we’d both be knee deep in whores and liquor about this time.”

I give the round one a sideways glance as he passed and peered into the back of my wagon. “‘Boy back here, Georgie.”

“White’r nigger?”

“My other boy.”

The round one hitched up and inspected Charles. “He dead? He ain’t moved a lick.”

“Asleep,” I said, with a croak in my throat.

“Damn, boy sure can catch his winks,” the round one laughed.

“Wha-choo two fellas looking for?”

The skinny one gave daddy a squint for a stare. “Who says we’re looking for something?”

“The time of day says so. Your demeanor says so. You ain’t known for these woods says so. You got gripes with a foreman, which means you’re on pay to be out here. You got interest in what’s in my wagons. You want me to go on?”

The round one continued to the back of my wagon. “We’s taking a coffle west. Ain’t our normal practice. We’s the handlers for market. Nigger gets sold, and we collect payment and guard the money.”

“But your foreman hired wrong.”

“Yep,” the skinny one said. “Coffle men didn’t show, so me and Benny and another fella name Stanley got volunteered to march the merchandise to the Miller Plantation.”

“Miller? Not familiar.”

The skinny one shrugged. “Don’t know enough to know what’s what around here. Rich fella is all I know. Paid above market for 16 farmhands and four breeders. A couple of pups, too.”

“None of this explains why you’ve stopped my travels.”

The skinny one adjusted his position in the saddle. “A breeder and pup got loose.”

I couldn’t see Daddy’s face, but I could tell that he said with a grin, “It appears your foreman does hire wrong.”

The skinny one took great offense at daddy’s comment. “Mister, maybe you ain’t noticed, but I’m strapped with a Navy repeater. Benny, too.”

Again, I could feel daddy’s grin. “I noticed. I also noticed you ain’t capped the chambers, which makes your weapons as lethal as sticks.”

The skinny one went cockeyed with confusion before turning his gaze down to his holstered pistol.

“The boy will tell you what you wanna know.”

I froze. I weren’t sure I’d heard daddy right at first.

“Tell ‘em, Augustus.”

I couldn’t form so much as a peep of a sound.

The round one spoke up. “You see something, boy?”

“I” was the only word I could cough up.

“Your boy ain’t talking,” the skinny one said.

“Augustus,” daddy said, eyes bloodshot with rage. “Speak up!”

I studied his hate-filled gaze. He’d seen the woman. Clear as day, but he wanted me to be the one who give up her location. He wanted me to be the cause of the beating coming her way. Not because he didn’t want it on his heart because he ain[t got one. He just wanted to corrupt mine.

Irked by my silence, daddy grumbled. “Boy, I will pound you to the devil if you don’t speak on what you seen.”

I closed my eyes in an extended blink and give rise to a hopeful thought the woman had found some distance from when I’d seen her last. “Seen a woman. Quarter tick back or so. Just off the path.”

“She have a young’un in tow?”

I shook my head.

“You sure on that?” the round one asked.

“She was by her lonesome,” I said, despising the words as they left my mouth because it meant she didn’t have no one to keep her secret. Not even me. A boy who’d seen her as tortured kin. She truly was alone.

The skinny one coaxed his horse around our wagons, all the while stealing glances at his sidearm to see if he’d truly forgotten to cap the chambers.

I watched as they galloped towards the woman’s sycamore haven, only turning away when I heard Daddy whistle and encourage his bay to take up our travels again. I asked the same of my horse.

Never taking his eyes off the path, Daddy simply said, “Property’s property, boy. You’lda been no better than a thief if you didn’t give that nigger up.” We were back to our slow-paced trek, leaving the doomed destiny of the runaway behind us. My hatred for daddy grew with each step my bay took. I’d give all the good luck the world had left to give me to get my hands on his mississip’ and plant a minnie ball dead-square in the back of his leather neck.

The First Plantation

When it come time for me and Charles to swap, I didn’t have no trouble sleeping. When I woke it didn’t feel like but five minutes had gone by, but it was a full two hour or so. We was turned up the trail to the Stephen’s plantation, a rambling 400-acre tea farm. Huge Magnolia trees lined both sides of the long straight road leading to the enormous pillared white house. It was as if an army of most-Southern giants was stepping aside to let us pass.

I climbed from the back of the wagon and took a seat next to Charles.

“I ain’t never had a tea in my life,” Charles said. “You?”

“Not that I can put memory to.”

“Mr. Stephens got more money than the lord above growing a thing me and you ain’t never had.”

“So.”

“Don’t add up is all. You figure to have this much money, every living body shoulda had at least a taste of his tea.”

“Plantation goes back a hundred years. His daddy’s daddy built it up.”

“How you know a thing like that?”

“Davidson told me.”

“Davidson don’t know true. He’s always telling stories.”

“Just ‘cause they’s stories don’t mean they ain’t true.”

A slave in a stocky frame come running from around the side of the main house, waving us down. “Morning, Mr. Tennyson!”

“Bernard.”

“Master Stephens wanted me to get your attention before you got underway at the coop, sir.”

“What fer?”

“He wanted to get a word with you, sir. Has a matter he wants to discuss with you, he says. I’m to take you ‘round back to the breakfast gazebo, sir.”

“Breakfast gazebo?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Who the hell has a gazebo just for breakfast?”

“It’s Lady Stephens invention, sir. Gets her closer to God’s providence, she says.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“What does what mean, sir?”

“God’s providence. What in the Sam Hill is that?”

Bernard considered Daddy’s question and then shrugged. “Don’t know, sir. I never thought to ask. It’s just something she’s been known to say from time to time.”

Daddy climbed off the wagon and stretched his legs. “Let’s get on with it, then. Take me to this breakfast gazebo so we can move onto our labors. Got a lot more travels ahead of us.”

“Yes, sir,” Bernard said without moving.

“Let’s go, Bernard. I gotta get on with my day.”

“Yes, sir. It’s just that Master Stephens wants to speak with all y’all. The boys, too.”

“My boys? Why?”

“He didn’t say, sir. He said I was to bring you and your boys to the breakfast gazebo soon as you arrived. They’s made up biscuits and jam for the lot of you.”

Charles and I both perked up at the news of biscuits and jam.

“He don’t have need to speak to my boys.”

“But I was instructed to bring them along, sir.”

“I don’t give a damn about your instructions. Now, let’s get.”

“But Master Stephens was keen on the boys’ presence.”

“Are you back talking me, Bernard?”

“No, sir. It’s just that I’m to do as Master Stephens says. I can’t get caught falling short on his instructions. It ain’t good for me, sir.”

“Daddy?” I said.

Daddy directed his ire from Bernard to me. “Didn’t nobody invite you to talk, Augustus.”

“Yes, sir, but you always say for-hires ain’t of no use if they don’t do their work without question or complaint.” The thought of biscuits of jam give me fuel to talk out of turn. I was inviting a beatdown, but I was too damn hungry to care. Let it be my last meal.

“What’s your point, boy?”

“Ain’t we Mr. Stephens for-hires?”

His face twisted into an even deeper frown than what normally rested below his dented nose. I didn’t know if he was mad because I had used his own notion against him or because I had reminded him he was nothing but for-hire laborer who answered to a boss. Daddy thought himself a magnate in the making. Working for a man, independent as the arrangement was, did not sit well with him, even if he was getting the better end of the bargain they’d struck.

Eyeing me, Daddy said, “You boys get down off the wagon.”

Me and Charles hurriedly jumped to the ground and stood at attention like we had just been inducted into the army.

“Let’s go, Bernard.”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“Don’t thank me, just take me to this gazebo, so my boys can eat your master out of biscuits and jam. You hear me, boys. This is your pay for the day. You eat so much that Stephens won’t never ask for your presence again. Stuff your guts.”

“Yes, sir,” Me and Charles barked.

We run ahead of Daddy and followed closely behind a well-paced Bernard. He’d learned to walk fast, and even at his long years, he moved quick as a cat.

Built on an on-high manmade mound, gazebo gazing meant you took in a full view of the properties back forty. A field of dark green, thigh-high tea plants stretched to a line of Cyprus trees. The field was unattended as it was Sunday, but every other day of the week, two dozen or more field hands was burning away the day, tending to the crops.

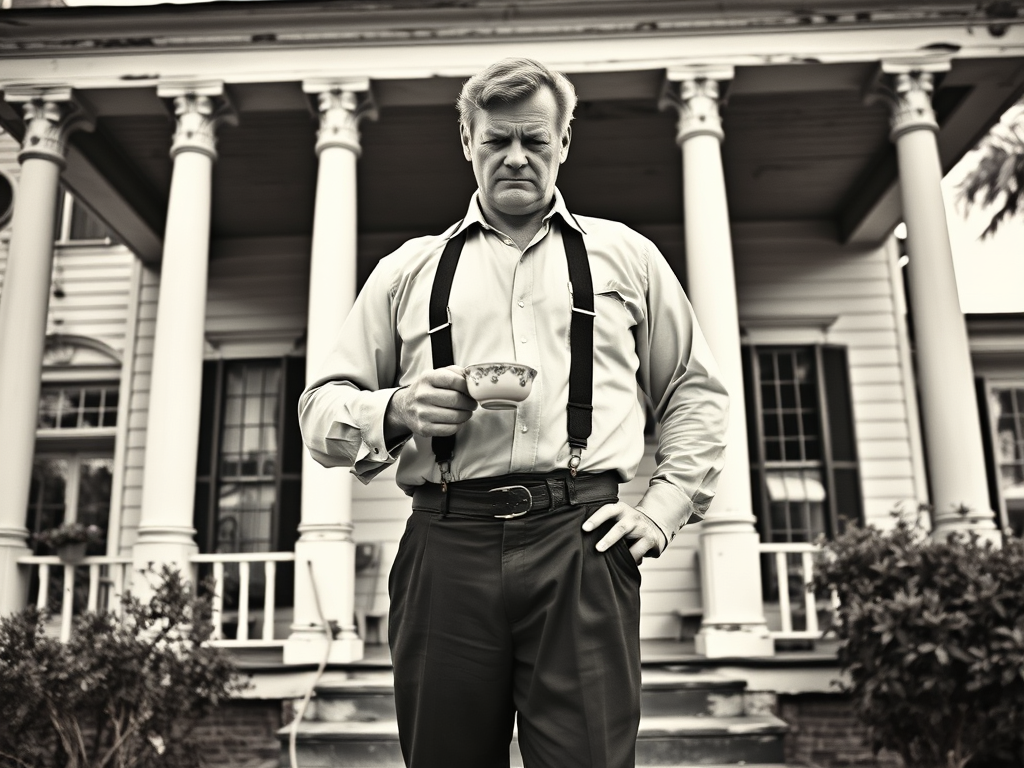

Mr. Stephens saw us approaching and stood from the over-stocked breakfast table. He was dressed as if he was setting off to church, but the nearest one was a three-day ride. “They have arrived. The honorable Horace Tennyson and two of his most handsome boys.”

“They just pulled up, Master Stephens. I fetched them right away, just as you said.”

“Fine work, Bernard. Fine work.”

We reached the stairs leading up to the gazebo and stood nervously. Daddy had removed his hat and was fiddling with the brim. “Good morning to you and yours, Mr. Stephens.”

Mrs. Stephens smiled down at us from her perch at the table. Her colorful bodice, adorned with silk flounces, seemed a touch too fanciful just for taking a meal on a gazebo past sunrise. “Oh, my Lord, those are some handsome boys indeed. Come on up here, boys. We have quite the spread this morning.”

We both turned to Daddy before accepting her invitation. He nodded, and we sped up the stairs. Daddy stayed with his feet planted on the ground.

“Coffee, Horace?” Mr. Stephens asked.

“No, sir. Thank you.”

From my vantage point in the gazebo, daddy looked smaller than I’d ever seen him.

“Tea, then?”

“No, sir. Thank you, Mr. Stephens.” I looked at Bernard standing next to Daddy and it struck me that they shared the same hangdog posture.

“Finest tea in all the Carolinas. You sure?”

Daddy done something I’d only seen him do under the weight of whisky. He laughed. It wasn’t much of a laugh. It was more of a jolly snort, but it was the first time it come out of him when he was cold sober. “I know, sir. Me and the missus have a cup every night. I can tell you that. A finer tea I ain’t never had.” Daddy, of course, would never waste drink on anything other than liquor. He’d never so much as sniffed a cup of Mr. Stephens’ tea. I now knew why Daddy didn’t want me and Charles accompanying him to the gazebo. He didn’t want us to see him lick a rich man’s boots.

“Well, join us all the same, won’t you?” Stephens said, motioning for Daddy to climb the stairs to the gazebo.

Daddy give Bernard a quick look and then done as requested. Standing on the deck of the gazebo, he bowed his head to Mrs. Stephens. “Ma’am. You are looking well-garnished this Sunday morning.”

“Why thank you, Mr. Tennyson. You are too kind. I only caught wind you were arriving an hour ago. I barely had time to dress and direct the kitchen staff to throw a decent meal together. My husband really should have given me more notice of your visit.”

“Oh, it’s not a visit, ma’am. Me and the boys are here to work.”

I looked at Charles. His cheeks was stuffed full with biscuit, and strawberry jam stretched around his mouth entire. We were both as happy as we’d ever been.

“Still, Mr. Stephens should have given me fair warning.”

“The foods more than ample,” Daddy said. “I’ll be bringing two fat boys home to my wife.”

Mr. Stephens pulled a chair out. “Have a seat, Horace.”

As anxious as he was to get to work, Daddy didn’t put up no fight to Mr. Stephens’ newest direction. He took a seat like a well-beat dog.

“I asked Bernard to escort you back here because there are a couple of matters I wish to discuss with you.”

“I hope they ain’t unpleasant matters, sir.”

“No, no, no, not at all. In fact, I’m trying to prevent some unpleasantness.”

“I’m in favor of that, Mr. Stephens.”

“Good, good. Tell me, do you have influence over a man by the name of Roland Dillard?”

“Dillard, sir? Influence?”

“He’s made claims that you and he are friends? Is that true?”

“Friends? No, sir. We ain’t. I’ve known Dillard a lot of years, but only as a vagrant who roams my property every growing season looking for wages.”

“Oh, that is a shame. I was rather hoping you could have a word with him for me.”

“He’s made himself a nuisance, has he?”

“Indeed. He is a lazy sort, as his kind is.”

“Mr. Stephens!” Mrs. Stephens scolded. “You mustn’t speak in such general, hate-filled terms.”

“Lidia, I cannot help but speak the truth. His indigent breed is a loathsome bunch who do not lend themselves to honest labor for honest pay. It is just a fact. Is it not, Horace? Am I out of line?”

“No, sir. With respect to Mrs. Stephens. My apologies, ma’am. Dillard is a no-account that has aligned himself with other no-accounts, and they’s a whole hornet’s nest full of them out there with the same no-account attitude. They have this idea that they’s entitled to fair pay because they’s white. All their skin tone entitles them to is a life without shackles and whip. Fair pay comes from hard earned work and what profit will allow.”

“Well, said, Horace! Well, said, indeed,” Mr. Stephens raised his coffee cup to toast Daddy’s grand declaration. He took a sip and continued with his complaints about Dillard. “Whenever these no-accounts, as you so accurately describe them, show up on my property, they mix in with the slaves in the evening, who proceed to trade off some of our food stores for cheap whisky. My negroes are far less productive for weeks on end after a visit from the likes of Roland Dillard.”

“That is unfortunate, sir. It truly is.”

“Yes, unfortunate. I have recourse to correct my slaves’ behavior, but there is nothing I can do about the behavior of Dillard. My overseer retires in the evening, and his foremen are stretched thin as it is. Short of posting a century at every slave’s quarters, I am but a horse’s tail swatting flies off my ass.”

Me and Charles giggled up a storm, covering our mouths, careful not to eject biscuits and jam onto the table.

“William Frederick Stephens! Such language in front of the children.” Mrs. Stephens scolded once again.

“She’s resorted to using my full name,” Mr. Stephens said with a big ol’ chuckle. “I’m to pay plenty when y’all have left, which gives me temptation to ask you to take up permanent residence here and save me severe admonishment for my remarks.”

“They are a farmer’s boys,” Daddy said. “I am sorry to say that I cannot promise they’ve been spared such language, and worse, Mrs. Stephens.”

“None of it said in front of a lady, I’ll wager.”

“No, ma’am. Just my wife.” Daddy’s face turned beet red because he spoke before thinking. “That is to say, not a lady such as yourself, Mrs. Stephens.”

“You are too kind, Mr. Tennyson. As I have not met your wife, I can only take mild offense at your slight towards her. It is my husband’s fault for introducing vile language on the Lord’s day in the first place.”

“My apologies to all,” Mr. Stephens offered up.

“About Dillard,” Daddy said, hoping to end the conversation and get on with our work. “I’d be happy to give him a talking to the next time he comes around my place.”

“Do you think it would help?” Mr. Stephens asked.

“Well, sir, to put it frank, I ain’t a rich man. Ain’t go the adornments you got. Can’t afford slaves, ‘cept the lot I lease from Judge Gadsden come harvest, and men of his sort ain’t a fan of slavery because of the pay it costs them. All the things I ain’t got gives me more weight with a man like Roland. My word just might have more sway over him than yours. If you don’t mind me saying so, sir.”

“If you can persuade him to keep clear of my negroes, I don’t mind at all. Not in the least. In fact, I’d owe you a debt.”

Daddy grinned at the idea of being owed a debt by a man like Mr. Stephens. He stood and excused himself. “The boys and I should get to our labors.”

“Hold on,” Mr. Stephens said. “I’ve one more matter to discuss. My house boy, Davidson, did he pass through your property a few days back?”

“Davidson?” Daddy said, pondering the question.

“He did, sir,” I said, piling jam on a biscuit. The words come out of my mouth without a thought. Davidson always passed through our property on his way to Charleston proper. I didn’t think nothing of it. He usually got daddy’s permission ‘fore doing so, but daddy was deep into bottle number two by the time he come through, so I just give him the go ahead. Forgot all about it until this moment, sitting in a breakfast gazebo, cramming biscuits and jam into my mouth.

Daddy looked at me. Brow furrowed.

“You saw him?” Mr. Stephens asked.

“Yes, sir. Said he was on his way to pick up some papers at the port he was to guard with his life.” As the last word escaped my lips, I thought of the woman hiding in the woods. Had I just given another poor unfortunate soul up?

“That was his charge,” Mr. Stephens said. “He was due back two days ago. He’s missed it by a day before, but two days is not his habit.”

Daddy scratched at the scraggly tuffs of hair growing across his jawline. “Augustus, Davidson, say anything worrisome?”

I stopped mid-chew and stared at the state of my newest biscuit prey. I thought on the question. We didn’t have no real discussion about nothing important. He rested a bit and we talked on a five-footed frog he swore he seen once, but beyond that there weren’t a thing worth repeating. He had him some ideas about rich folks, too, but nothing bad. “No, sir. Davidson just made mention of the papers and how rich folks seem partial to papers about this and that. Nothing more was said, other than his desire that you not shoot him for crossing our property.”

“Did he show you his travel papers?” Mr. Stephens asked. “I instructed him thusly. I told him not to disrespect my neighbors by crossing their property without permission and proof of his travels on my behalf. Did he at least follow those instructions?”

“Yes, sir, he did. I told him such a thing weren’t necessary on my part.”

Daddy fought back a grumble in the presence of Mr. and Mrs. Stephens. “Why did you tell him that, son?”

I hated it when he called me that. I fought back my own grumble. “’Cause, sir, I know Davidson. Known him my whole life. He comes to and fro on our property all the time. He’s always on business for Mr. Stephens.”

Daddy give Mr. Stephens a fake reassuring grin and then did his best to take on a gentle tone. “You’re always to get proof of travels of any negro coming through our property. You hear me? It don’t matter if you know’em or not. They’s always scheming to run.”

“Yes, sir.”

Mrs. Stephens interjected and stroked the top of my head. “I think this is all worry about nothing. The shipment was just delayed. That’s all. I’m sure of it. The ocean is a treacherous journey, even for a piece of paper. Its arrival was put off by two days or more, which explains Davidson’s late return. I’m with Augustus on this matter. Davidson is wholly trustworthy.”

Daddy give a stiff-neck nodded. “I’m sure he was well trained and with a loving hand, Mrs. Stephens.” He stood. “Now, if it’s all the same to you, the boys and I have labors and travels that we will scarcely be able to fit in by next sunrise if we don’t get to them now.”

Mr. Stephens stood. “Of course. We appreciate the time you spared for us. I’ll have Bernard wrap up the rest of these biscuits for you and the boys to take with you.”

“That won’t be necessary, sir,” Daddy said.

“Nonsense. You’ve agreed to help me with my Dillard problem. Food for the road is just a small token of my appreciation.”

Daddy nodded. “You’re too kind, sir.” He give a half bow to Mrs. Stephens. “Ma’am. May you enjoy God’s providence in peace this glorious morning.”

Mrs. Stephens blushed. “I surely will, Mr. Tennyson. I surely will. And tell Mrs. Tennyson she has raised some mighty fine boys.”

“Mighty fine fat boys, thanks to your generosity. Boys, thank Mr. and Mrs. Stephens for the biscuits and conversation.”

Me and Charles thanked them, bashful and excitable all at once and then bounded down the stairs in pursuit of daddy, who was in a near foot race to the wagons. He disappeared around the corner before we’d taken more than a few steps from the gazebo. When we come into view of the wagons, he was nowhere to be seen. I was just about to ask Charles where daddy had gone when I felt a boot to my backside. The pain was so high on that I fell to the ground, barking out in agony. Daddy knelt down beside me and placed his hand over my mouth, madder than a wet hornet.

“Boy, you ever let a nigger pass through my property again without checking travel papers I will kick your scrawny ass inside out.”

My eyes welled-up with tears, and I seen Charles back away as if a rattlesnake was ready to strike him.

“You are trouble, boy. You don’t do nothing but sass me and fight me on every little thing I tell you to do. You keep at it and you ain’t going to see your birthday next. You hear me?”

I nodded and fought the urge to tell him ain’t a thing ever done to celebrate my birthday anyhow.

He removed his hand from my mouth and stood. “Now, we’re gonna get on with this trade-out quick as we can and move on. Not another word from the two of you. I got no problem bringing your momma home her newly departed boys. You understand me?”

I stood with difficulty and stifled the signs of how much pain was running rapids through my body.

“Your Momma has got some breeding years left in her, and I could get two more farmhands from her that won’t be nearly as much trouble as the both of you, and I’ll see to it that they do twice the work. She made me be too easy on the two of you. Any new pups pop out of her, I fer damn sure won’t be making that mistake again.”

He made a motion for the wagons, and Charles flinched as if a fist was being thrown in his direction. Daddy shook his head. “This one’s scared of his shadow, and the other ones got a mouth that won’t stay shut. The devil cursed me double the days you two were born. I can tell you that.” He climbed on his wagon. “Get on your rig and follow me. Now.”

Me and Charles showed no haste in following his instruction. I gingerly took my seat and zeroed in on the back of Daddy’s neck again. Oh, how I would’ve loved to see a rope hanging around it and him swinging from a tree.

Leave a comment