The Last Plantation

Pritchard’s plantation was the smallest of our stops. It measured out to a paltry 174 acres, and everyone who knew the place agreed Thomas Pritchard mismanaged the piss out of it. He grew rice like Daddy, but unlike Daddy, he didn’t have much in the way in what they call aptitude for such matters. Daddy made claim that Pritchard hired and fired more field managers than he’d actually grown grains of rice.

When we pulled up the path to the main house, there was no splendor to it like visitors experience at the Stephens plantation. It felt less respectable than even our tiny little speck of a farm.

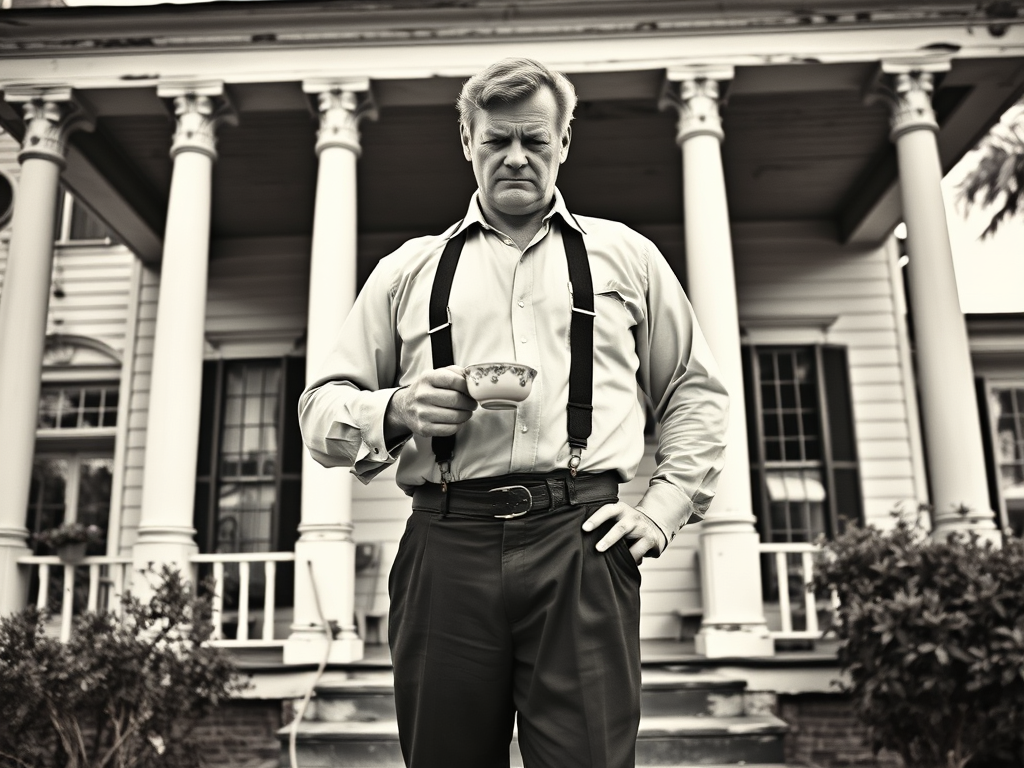

A man of rugged trade approached our two-wagon caravan before we reached the house. He was tall, broad of shoulder and thick in the waist. His face was red and weathered by the sun and hard times. “Can I help you?”

“Name’s Tennyson. Mr. Pritchard is expecting me.”

“You missed Pritchard by three weeks.”

“Missed him? What’s that supposed to mean?”

“He sold the place. Moved on.”

“Sold the place? To who? To you?”

“Nah. I’m just the advance man. Sold it to my boss.”

“Who’s your boss?”

“Cameron Miller.”

“He around?”

“Nah. Told you. I’m the advance man. Mr. Miller ain’t do for another month.”

Daddy dropped his chin to his chest and let out a groan. “Well, if that don’t beat all.”

“What kind of business you have with Pritchard?”

“We brought fresh litter for his coop.”

The big man looked over our rigs. “You come a long way?”

“Started before sunup. Won’t be back home until tomorrow sunup.”

“These your boys?”

Daddy turned to us. “Yeah, sir. Charles and Augustus.”

The big man surveyed our rigs one more time before huffing and shrugging. “Litter needs changing. You charge Pritchard a fair price?”

“Six bits. New litter in. Six bits more, old litter hauled away.”

“Six and six? Pritchard was robbing you blind.” He placed his hands on his hips. “I’d be a fool to not rob you at the same price.”

Daddy tipped his hat. “You’re a good man, sir.”

“Nah, I ain’t. If I was a good man, I’d be paying you a good stretch more than a dollar and a half.” He turned to head back to the main house.

“What’s Mr. Miller got planned for the place?”

The big man kept walking toward the house. “Can’t say for sure, but he’s most likely going to burn it down.”

“Burn what down?”

“The house. The barn. The coop. The slave quarters. They are in a terrible state of disrepair.”

“Mr. Miller a rice farmer?”

“Not as such.” He turned back to us when he reached the steps leading to the porch of the main house. “Farming does occur on the properties he owns, but it is not his primary source of income.”

“What is then?”

“He’s a breeder.”

“Of what? Bovine? Horse? What?”

The big man smiled and pointed one of his meaty index fingers at Daddy. “Did you come across a coffle in your travels today?”

Daddy sat up straighter. “We did. Well, we come across two men assigned to drive the coffle.” Daddy snapped his fingers. “To the Miller plantation. This was where they were headed?”

“No,” the man said. “Stopped off here, they did, on their way to Mr. Miller’s other purchase 15 miles or so east of here.”

“Other purchase?” Daddy seemed unsettled by this news. “This boss of yours? He from around here?”

“Nah. Alabama. Montgomery. Born and bred.”

“Why the interest in South Carolina?”

The big man smiled. “Laws and lawmakers are more amenable to Mr. Miller’s business practices.”

“That, so?” Daddy said, sounding even more concerned.

“It is. Anyway, I heard tell of a man and his boys helping two of those idiots in charge of the coffle. Nigger girl and pup got loose. I’m assuming you are the man and his boys.”

“We are. They find the runaways?”

“Found the breeder. Not far from where you said she was. Pup is still on the loose. I expect Mr. Miller will write her off. Young’un like that in these woods will be dead by week’s end.”

“The breeder’s in fair condition?”

“She was until she got found. Dropped her off here to convalesce. She’ll live. Mr. Miller will be pleased you saved his investment.”

Daddy nodded before driving his rig towards the coop. “Glad to help out a neighbor.”

My stomach tied up in hard coiled knots as we drove away. I’d cost the woman a beating. Daddy would say she wasn’t nothing more than property that wasn’t worth fretting over, but her pleading eyes was etched permanent in my mind. I led the cruelty she was on the run from straight to her. The claim that she wasn’t nothing but property by men like daddy didn’t hold rule over me. I’d betrayed a fellow sufferer.

The coop was in an awful state, and the smell of it come known to us long before we pulled our wagons to a stop. If this Mr. Miller had plans to burn it, as his big advance man predicted, a better use for fire had not been invented.

The two bays fidgeted and snorted as we all climbed off the rigs. “Horses seem agitated,” Charles said.

“They are that,” Daddy said. “Theys need watering. Augustus, head back to the house, and ask Mr. Miller’s advance man if he’d allow water for our bays.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Move fast and no messing about.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Be on your best. Don’t want word getting back to Mr. Miller that his neighbors are trouble.”

“Yes, sir.”

I waited for any last instructions as Daddy seemed extra concerned that Mr. Miller’s advance man be addressed in a particular manner so as not to cause woe.

“Did I not say to move fast, boy?”

“Yes, sir,” I said as I turned and sprinted towards the main house. I ran as fast as my legs could carry me, skipping steps on my way up the front porch, tripping on the top step and stumbling before righting myself and standing in the open doorway.

“Mister?”

There was no answer.

“Mister?”

Nothing. I ducked my head inside. “Mister advance man?”

Still nothing.

My Daddy’s voice rang out in my head. Move fast and no messing about. Turning back with claim I couldn’t find the advance man was not a position I wished to find myself. I put one foot past the threshold and leaned inside. “Our horses need watering.”

A noise came from my right. I turned to see a what was once a fancy sitting room now rundown to a state of shambles. The swanky furniture was faded at the fabric and cracked at the wood. Pritchard did more than mismanage the piss out of his farm. He made a wreck of the innards of his home, too.

A groan come from the room. I shifted my gaze in the sound’s direction and decided it come from the couch, of which I had the backside view. My foot took on a mind of its own and planted itself deeper inside the house. I stood full and upright, raising up on my toes to get a look at who or what was lying on the couch.

A second groan. It was not the advance man.

I should’ve called out again, but something inside me kept me silent. Curious and afraid all at once, I took one step towards what was nothing else but the sounds of a person in agony. Another step followed. I made no effort of thought to take these steps. They just occurred without my say. In the time it took me to blink, I found myself in the position to see over the back of the couch. There lay the woman I’d seen pressed against a sycamore tree in the woods. Her once pleading eyes swollen shut. Her nose busted to a pulp. The blue dress torn and savaged. The white of her collar turned crimson. Her hands remained bound at the wrist, and her legs were now bound at the ankles. Looking at her, I felt as sick as I’d ever felt in my life. Even the snake bites that’d driven me to near death did not feel so bad as the scene of the poor soul shattered beyond recognition because of me. She heard the floor creak beneath my last step and turned her battered head to me in a panic. The groans turned to a wail. Her eyes were so busted up she couldn’t see me, even though I weren’t but a few feet away. I’m ashamed to admit it but I found comfort that they had beaten her blind and unable to recognize me ‘cause it meant I could hide like the coward I was.

“Get a good look, boy?”

The big man’s voice boomed from behind me. I felt my ribcage rattle and my knees buckle. I couldn’t find the balance to turn and run. Instead, I stumbled as I twisted toward the front door and tripped over my own feet. Falling to the ground with a thud, I immediately scrambled across the floor on my hands and knees until I found the sense to stand and then I run as fast as I could, bolting out of the house and racing down the stairs. My lungs felt like they was on fire. Daddy would give me a beatdown for not getting permission to water the horses, but I didn’t care. I deserved it for what I’d done to that poor woman.

Leave a comment